From the Hooker family have come two great 16th century figures - John Hooker, writer, lawyer, historian and political administrator, and his nephew Richard Hooker, theologian, priest and writer - and two of the greatest 19th century botanists, Sir Wiliam Jackson Hooker and his son Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker: the Hookers of Kew Gardens.

The Hookers

The Hookers are different from other families of this site insofar as I have not conclusively tied my Hookers to the family members appearing here. My g-g-g uncle William Berry's second wife Susan Boddy (1814-1893) was the daughter of a Hooker who was alleged to be descended from the famous Hooker family. A history of the Berry Family written in 1965 claims that, "The family tree of Susan Boddy...definitely reaches down to her from Richard Hooker, the famous Exeter theologian..." The trail that I have followed from Susan has so far led to Seraphin Hooker, brushmaker of Exeter, born about 1760. I have constructed speculative links between that Seraphin, and John and Richard and the Kew Hookers' family. But the links are just that - speculative. I would appreciate any help with Seraphin's antecedents, to confirm or disprove my speculations. In fact there are two links to Seraphin, as Eliza Hooker Berry, daughter of William and Susan Berry, married Daniel Cragg Hooker, who was also descended from Seraphin.

The Hookers originated with the Vowell familyof Pembrokeshire and moved to Devon, where after marriage to an Alice Hooker the family took the name Hoker or Hooker in preference to the Welsh family name Vowell, though both names were used.

John Hooker (c.1526-1601)

John's grandfather John Hoker was Exeter Mayor from 1490-1491, and Exeter's MP for many years. His father Robert was Mayor of the city from 1529-1530. So John was born into a prominent family. His father died from plague in 1537, leaving the boy well provided for. He was educated at Oxford, and then continued his education in Europe. He studied law at Cologne and lived for some time in the house of Peter Martyr at Strasbourg, attending the great theologian’s divinity lectures. He married Martha Tucker in the 1540s. This was a time of religious turmoil in England. In 1549 he witnessed the siege of Exeter during the Prayer Book Rebellion, when Cornish Catholics joined with colleagues in Devon to oppose the imposition of Anglican worship and the new Prayer Book in English. Exeter was besieged for five weeks and the historian in John ensured that he left a vivid account of the events, making no effort to conceal his religious sympathies, as John was openly and vocally Protestant, which in later times must have posed some risk for him. He worked for the Bishop of Exeter briefly. Then in 1555 he was made the first Chamberlain of Exeter. His role included managing disputes between guilds and merchants, and the overseeing the city's finances. One aspect of this was administering the estates of the orphans of deceased freemen. In this role he was allowed to retain one third of all money paid out to the orphans from their estates. This made him very rich - something that was resented. He was the last Chamberlain to have those powers! He also oversaw the rebuilding of the high school, planted many trees in the city, and collected and put in order the city's archives. These archives enabled him to compile his "Annals" of the City, about every Tudor mayor of Exeter, and in 1578 he wrote The Lives of the Bishops of Exeter.

In 1568 he went to Ireland as legal adviser to the Devonshire adventurer Sir Peter Carew who had dubious claims on an Irish Barony. Whilst there Hooker was made a member of the Irish Parliament. Then in 1570/71 he was made an MP for Exeter. His experience in both parliaments gave him material to write a study of parliamentary practice. He spent much time in Ireland, but returned to Exeter where in 1583 he was made coroner, and in 1586 he again represented the city in Parliament. He was one of the editors of the second edition of Holinshead's Chronicles, published in 1587. One of the great works for which he is remembered was The Antique Description and Account of the City of Exeter: In Three Parts, All Written Purely by John Vowell, Alias Hoker. He began a topographical description of the county of Devon, but was unable to finish it before his death. Writing to the Exeter Corporation just before his death, he described himself as ‘unwieldy and imperfect ... my sight waxeth dim, my hearing very thick, my speech imperfect and my memory very feeble’. He died between 26 January and 15 September 1601, and was probably buried in Exeter cathedral. But he did manage to find time during his life to exert some influence on behalf of his nephew, Richard Hooker.

Arms of Hooker als Vowell

John Hooker 1591

Richard Hooker 1554 - 1600

John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury, Hooker's patron

Statue of Richard Hooker in Cathedral Close, Exeter

Road in Heavitree, Exeter, named after

Richard Hooker

Richard Hooker is known today as the prophet of Anglicanism, and a founder of Anglican theological thought. The nephew of John, he was born in 1554 in Heavitree, then a village to the east of Exeter. His parents were the poor relations of the family. He was recognised as an enquiring child. With the financial support of his uncle he was able to attend Exeter Grammar School. He showed great promise at school, and his uncle sought for him the patronage of his friend John Jewel, the Bishop of Salisbury. Jewel could ensure a place at Corpus Christi College which was well known for its liberal Protestant leanings. Jewel was the first major apologist of the Church of England.

Richard Hooker is known today as the prophet of Anglicanism, and a founder of Anglican theological thought. The nephew of John, he was born in 1554 in Heavitree, then a village to the east of Exeter. His parents were the poor relations of the family. He was recognised as an enquiring child. With the financial support of his uncle he was able to attend Exeter Grammar School. He showed great promise at school, and his uncle sought for him the patronage of his friend John Jewel, the Bishop of Salisbury. Jewel could ensure a place at Corpus Christi College which was well known for its liberal Protestant leanings. Jewel was the first major apologist of the Church of England.

At Oxford Richard gained both bachelor's and master's degrees, and was ordained into holy orders. His progress was obviously followed and approved of in Exeter, for the Mayor and Corporation in 1582 awarded him a pension of £4 per year "for as long as it shall please this house". He had gained a reputation as an able scholar and teacher, tutoring the sons of some of the most famous men in England, including the son of the Bishop of London, Edwin Sandys, a renowned Protestant, and the great nephew of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. Word reached Queen Elizabeth that Hooker was teaching a more tolerant version of faith and worship that fitted well with her own desires to build a broad church where Protestants and Catholics could worship without the violence and persecution that had been so much a part of English life since the Reformation. Richard was often embroiled in religious disputes. His position as a fellow at Corpus Christi meant that he was expected to enter into debate, and to preach at Paul's Cross at St Paul's in London, where notable liberal clerics would expound their theology. Richard's sermons there challenged Puritanism and he was regarded as controversial.

In 1584 he was given the living at St Mary's, Drayton Beauchamp, in Buckinghamshire. But he was not to stay long there, and probably spent barely any time there. Queen Elizabeth made him Master (Rector) of the Temple Church in the City of London in the following year. At this prestigious church judges, lawyers and powerful men of the city worshipped each Sunday. His sermons could not be but influential. Controversy followed him in this role, but he had the support of the Queen and the Establishment. He began to expound from the pulpit there the ideas that were to be set down and developed in his great book Of the Laws of Ecclesiatical Polity. He seems to have begun writing the book in about 1586. In 1591, Hooker left the Temple and was given the living of St. Andrew's, Boscomb in Wiltshire, to support him while he wrote. He had probably set down the draft of the entire work by that date. He lived mainly in London but apparently did spend time in Salisbury where he was Subdean of Salisbury Cathedral, and made use of the Cathedral Library. The first four volumes of Of The Laws were published in 1593.

He probably met his wife to be Joan , daughter of John Churchman, a distinguished London merchant, who became Master of the Merchant Taylors Company in about 1584. He married her in about 1588. Early biographers have suggested that his marriage was a failure, his wife a scold and he had made the mistake of marrying his landlady's daughter. The evidence does not support this. Hooker lived with his wifes parents for some 6 years, and they seem to have been a considerable support and help to him. He had four daughters and two sons with Joan, but they all died in infancy or before the age of 20, except the eldest daughter Alice.

He probably met his wife to be Joan , daughter of John Churchman, a distinguished London merchant, who became Master of the Merchant Taylors Company in about 1584. He married her in about 1588. Early biographers have suggested that his marriage was a failure, his wife a scold and he had made the mistake of marrying his landlady's daughter. The evidence does not support this. Hooker lived with his wifes parents for some 6 years, and they seem to have been a considerable support and help to him. He had four daughters and two sons with Joan, but they all died in infancy or before the age of 20, except the eldest daughter Alice.

In 1595, Hooker became Rector of the parishes of St. Mary the Virgin in Bishopsbourne and St. John the Baptist, Barham in Kent, and left London to continue his writing. He published the fifth book of Of the Laws in 1597. He died 3 November 1600 at his Rectory in Bishopsbourne, and was buried in the chancel of the church, being survived by his wife and four daughters. The final three volumes of his mighty 8 volume work were published posthumously.

His will includes the following provision: "Item, I give and bequeth three pounds of lawful English money towards the building and making of a newer and sufficient pulpitt in the p'sh of Bishopsbourne." The pulpit can still be seen in Bishopsbourne church, along with a statue of him.

Hooker's prose is admired for its sophistication and clarity, his immense legacy to theology the notion of a church founded in the Scripture, reason and tradition.

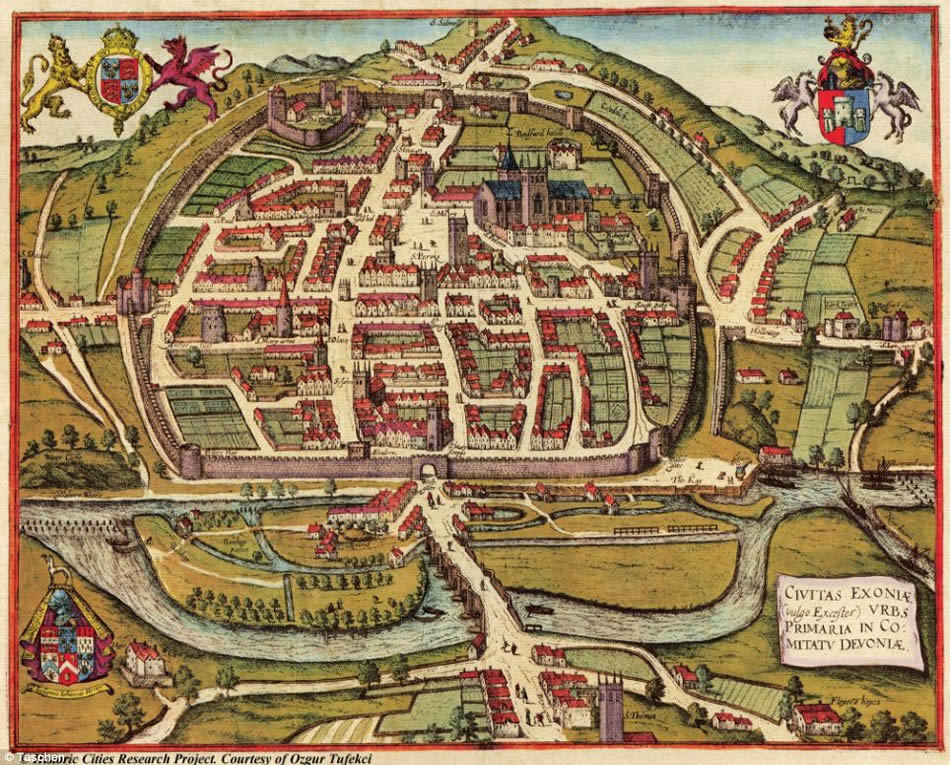

Sixteenth century Exeter

Sixteenth century Exeter

Sir William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865)

William was the son of Exeter clerk Joseph Hooker who was working for the future banking family, the Barings, at that time successful merchants. The Barings sent him to Norwich to establish a bombazine business in connection with the East India Company's trade. He devoted much of his time to the study of German literature and the cultivation of curious plants. He married the daughter of a local weaver, and son William was born there in 1785.

William was educated at the local grammar school and later at Starston Hall, where he learned estate management. A very generous legacy from his godfather, William Jackson, left him with independent means that enabled him to travel and to take up as a recreation the study of natural history, especially ornithology, entomology and botany. It was probably when he discovered a new moss, Buxbaumia aphylla, subsequently confirmed by the brewer and botanist Dawson Turner as a new species, that his career specifically as a botanist began.

When he was elected a Fellow of the Linnaean Society at the age of twenty-one, he was introduced to Sir Joseph Banks the renowned botanist responsible then for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew , as well as many other prominent naturalists. Banks sponsored Hooker in an expedition to Iceland, all expenses paid, but the natural history specimens which he collected, with his notes and drawings, were lost on the homeward voyage through the burning of the ship, and the young botanist himself had a narrow escape with his life. A good memory, however, aided him to publish an account of the island, and of its inhabitants and flora (Tour in Iceland, 1809), privately circulated in 1811, and reprinted in 1813. In 1814 he spent nine months in botanizing excursions in France, Switzerland and northern Italy. As well as a close relationship with Banks, his relationship with Dawson Turner was also a close one that grew closer when he married Turner's eldest daughter, Maria, in 1815 and the couple settled at Halesworth in Suffolk.

Then with Joseph Banks' support, William Hooker was able to obtain the Chair of Botany at Glasgow University in 1820. During the twenty-one years of his tenure he revitalised the botany department as well as the city's botanical gardens. He was a popular lecturer. He began the Botanical Magazine in 1826. He was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order in 1836. In these years he increased his collections and laid the foundations of his herbarium, later to form the basis of the Herbarium at Kew. Eventually Hooker found that his income was not sufficient to support his growing family. He was a singularly social creature who cultivated many important friendships and maintained life-long correspondences with many of them. It was by exercising his many connections and influences that in 1841 he took over management of Kew and was appointed as Director.

Sir William had long felt that the Royal Gardens at Kew, which had fallen into neglect after Banks’s death, had the potential to become the centre of botanical science for Great Britain and its empire. He initiated the construction of several glasshouses, including the famous Palm House, and organized the garden's beds in a more logical and scientific manner. His other innovations included the Museums of Economic Botany, the Herbarium and Library, the admission of the public to the Gardens on weekdays, and the publication of an official guidebook. Over the years Hooker was able to use his considerable charm and tact to expand the garden by acquiring many of the surrounding royal grounds. The gardens expanded from 11 to 75 acres, with an arboretum of 270 acres. It was mainly by Hooker's exertions that botanists were appointed to the government expeditions. He maintained his position as director until his death in 1865 at which time his son, Sir Joseph Hooker, took over as Director. He was engaged on the Synopsis filicum with J. G. Baker when he was attacked by a throat disease then epidemic at Kew, where he died on the 12th of August 1865.

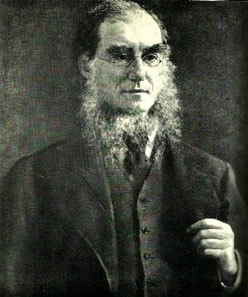

Sir William Jackson Hooker

Sir William Jackson Hooker

Joseph Hooker, father of William

The young Joseph Dalton Hooker

Rhododendrons collected and drawn by Joseph Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

Plaque on the Hookers' house in Kew

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817–1911)

Born in Halesworth, Suffolk, when his father was professor at Glasgow University, six year-old Joseph accompanied him to the university almost every day and attended his lectures, thus forming an interest in plant distribution. Another early enthusiasm was travellers’ tales – he recalled sitting on his grandfather’s knee, looking at the pictures in Captain Cook’s Voyages.

He was educated at the Glasgow High School,and went on to study medicine at Glasgow University, graduating M.D. in 1839. But his principal interest was botany. His degree qualified him for employment in the Naval Medical Service. He joined renowned polar explorer Captain James Clark Ross's Antarctic expedition to the South Magnetic Pole after receiving a commission as Assistant-Surgeon on HMS Erebus, for William's income would not allow Joseph to travel as a self-financed, gentlemanly companion to the captain as Charles Darwin had done on the Beagle. Instead as a lowly assistant surgeon he was subject to naval discipline and had many shipboard duties to perform.

Between 1839 and 1843, the Erebus, visited many places including Madeira, the Cape of South Africa and the Antarctic.They wintered in New Zealand and Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania). The trips ashore allowed him to collect plants in relatively unknown regions. When the Erebus returned to England in 1843 Hooker needed to find paid botanical employment. Although his father had been made the first Director of Kew, the appointment had reduced his income and he was still unable to give his son much financial support. Fortunately his influence was sufficient to secure an Admiralty grant of £1,000 to cover the cost of The Botany of the Antarctic Voyage's plates, and Joseph received his assistant surgeon's pay while he worked on it. The book eventually formed six large volumes: two each for the Flora Antarctica, 1844–7; the Flora Novae-Zelandiae, 1851–3; and the Flora Tasmaniae, 1853–9. Nonetheless Hooker's Antarctic publications never made any money, and much of his time in the 1840s was taken up with searching for paid employment.

Shortly after his return from the Antarctic, Hooker received a letter from Charles Darwin congratulating him on his achievements, and asking whether Hooker would be interested in classifying the plants Darwin had gathered in the Galápagos. These first letters marked the beginning of a lifelong correspondence, through which the two became friends and collaborators, and debated their many scientific interests. Darwin shared with Hooker his theory of evolutionary biology many years before On The Origin of the Species was published. Although the two would argue over questions such as plant distribution, Darwin trusted and respected Hooker and valued his opinions.

In 1848 Joseph obtained a government grant for a trip through northern India and Nepal. He surveyed the flora there and sent back specimens to Kew, managing to collect about 7000 species on that trip. Among them were some twenty-five previously unknown species of rhododendron, some of which can be seen in Kew's Rhododendron Dell. In Sikkim he and his colleague succeeded in annoying the elderly raja by crossing the country's borders into Tibet despite an injunction not to do so. As a result they were arrested and imprisoned in November 1849. The British government secured their release within weeks by threatening to invade Sikkim. His book The Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya was followed by two volumes of Himalayan Journals, and The Flora of British India, which were dedicated to Darwin.

On 15 July 1851 Hooker married Frances Harriet (1825–1874), eldest daughter of John Stevens Henslow, the Cambridge professor of botany who had taught Darwin. Joseph and Frances had four sons and two surviving daughters, but Hooker's favourite daughter, Minnie, died in 1863 when she was just six years old. Frances died in 1874 and in 1876 Joseph married Hyacinth Jardine Symonds(1842–1921), , with whom he had two more sons.

The 1850s also saw the appearance of several of Hooker's most important publications. These were largely taxonomic, concerned with classifying and naming new species and with reclassifying previously known ones. The herbarium and gardens at Kew had grown substantially since his father had been put in charge. When the government finally agreed that the director could not cope alone their decision gave Joseph the secure, paid employment he sought: he was appointed assistant director on 5 June 1855. In 1865 Hooker's father died and Joseph succeeded him as director of Kew. Hooker was by this time a highly regarded botanist with a worldwide reputation, though he might not have secured the position without his father's constant assistance. His contributions to the Gardens included the T-Range glasshouses, the first Jodrell Laboratory and the Order Beds, where the plants are arranged according to the Bentham-Hooker classification. Joseph remained director of Kew until his retirement in 1885.

The public function of Kew became a source of controversy in various ways under Joseph. He believed that the garden's primary objectives were scientific and utilitarian, not recreational, and he complained about the need to create elaborate floral displays for those he regarded as mere pleasure or recreation seekers. The role of science was paramount in his life. In 1873 he was elected president of the Royal Society, where he instituted various reforms designed to broaden public participation in the society, including the ladies' soirées. When he retired from the presidency in 1878 Hooker was particularly proud of the £10,000 he had helped raise which allowed the restrictively high membership fees to be reduced.

The full list of his publications was consdiderable. Some of the more important later ones include: Outlines of the distribution of Arctic plants (1862); the Student's Flora of the British Isles (1870); Genera plantarum (with George Bentham, 1860–83); the Flora of British India (1855–97). As well as writing he continued to travel, and visited Syria, Morocco and the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and Utah. He was highly regarded in his lifetime and received numerous honorary degrees including ones from Oxford and Cambridge. He was created CB in 1869; KCSI in 1877; GCSI in 1897; and received the OM in 1907. The Royal Society gave him their royal medal in 1854, the Copley in 1887, and the Darwin in 1892. He received numerous prizes and awards from both British and foreign scientific societies.

Hooker died in his sleep at midnight at his home, in Sunningdale, on 10 December 1911 after a short and apparently minor illness. He was buried, as he wished to be, alongside his father in the churchyard of St Anne's on Kew Green on 17 December.

Joseph being presented with plants in Sikkim

The Palm House at Kew Gardens